You Can't Go Back... to the Future

Ravage 2099 #1

writer: Stan Lee

penciller: Paul Ryan

inker: Keith Williams

colorist: Paul Becton

penciller: Paul Ryan

inker: Keith Williams

colorist: Paul Becton

*

If you were flipping through the September 1990 issue of your favorite Marvel title, you might have come across a fascinating tidbit in Stan Lee’s semi-regular “Stan’s Soapbox” column on the Bullpen Bulletins page. Here, Marvel’s beloved publisher revealed he was working with John Byrne on a project “featuring a never-before-seen superhero world.” In subsequent columns over the next few months, he unveiled a working title of "The Marvel World of Tomorrow," and raved about Byrne’s artwork for the project. He also revealed the hero would be a character called Ravage.

When I read this, it seemed too good to be true: The co-creator of the Marvel Universe and my then-favorite artist working a story about superheroes in the future? I waited with great anticipation.

Well, as it turns out Lee’s promotional efforts got ahead of the actual work. At some point, Byrne backed out of the project (it’s said he used some of the ideas on his 2112 graphic novel for Dark Horse, and the subsequent Next Men series), and the "Marvel World of Tomorrow" became "Marvel 2099," which launched with four books in late 1992.

According to Danny Fingeroth’s 2019 biography of Lee (A Marvelous Life: The Amazing Story of Stan Lee), the concept started as a potential reunion of Lee and his original Spider-Man and Dr. Strange collaborator, Steve Ditko. Lee had the idea of a futuristic world overrun by pollution, with trash collectors serving as superheroes of a sort. Ditko was surprisingly amenable to working with Lee again, but didn’t like the dystopian bent of the story (indeed, this was something rarely seen in comics, where the future was typically depicted as moving closer to utopia, as in DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes and Marvel’s own Guardians of the Galaxy). One assumes Byrne was next in line.

After Byrne bailed, the assignment fell to veteran artist Paul Ryan. The concept kept its ecological focus, but was wrapped in with other 2099 writers’ vision of a future that’s technologically advanced, but grimy and ruled by corporations. This allowed the line to focus on the “edgy” type of hero that was selling so well during the early 1990s. Ravage also survived from Lee’s initial idea, though he wasn’t quite a garbage man (though he does briefly drive a garbage truck).

Marvel 2099 debuted in November 1992 with Spider-Man 2099, and would be joined by Ravage 2099, Doom 2099, and Punisher 2099 in subsequent months. Of these, only Doom had an explicit connection to the present day. Ravage, on the other hand, was the only non-legacy character.

*

Stan Lee hadn’t written any comic books regularly since the late 1960s, but after being absent from the writing side of things for most of the 1970s and 1980s, he had been returning to the pages with more regularity. In 1988 he teamed with John Busecema for the Silver Surfer: Judgment Day graphic novel. He followed that up with a two-issue Silver Surfer story with legendary French artist Moebius in 1989. That same year he scripted a new take on a licensed character called Solarman (there was also a cartoon pilot for a show, but it was never picked up). And in 1991 he wrote a comic about a character called Nightcat, whose identity was real life singer Jacqueline Tavarez (there was even a Nightcat album).

Ravage 2099, then, was Lee’s first wholly new superhero concept in many years. The first issue introduces us to Paul-Phillip Ravage, of the “Commander” (akin to a CEO) of a company called ECO, whose mission is to fight pollution, seemingly by sending its bloodthirsty security force after “polluters” (again, in this future, corporations have essentially taken over public services). Trick is, they’re a subsidiary of Alchemex, a company that does most of the polluting.

This is an intriguing set-up, but Lee doesn’t seem all that interested in the inner workings or grander implications of the world he’s created. He only wants to get Paul-Phillip to his status as a kick-ass vigilante. So through a series of events not worth recounting, Paul-Phillip learns of his company’s misdeeds, gets framed by his boss, and is forced to go on the run.

Stan Lee hadn’t written any comic books regularly since the late 1960s, but after being absent from the writing side of things for most of the 1970s and 1980s, he had been returning to the pages with more regularity. In 1988 he teamed with John Busecema for the Silver Surfer: Judgment Day graphic novel. He followed that up with a two-issue Silver Surfer story with legendary French artist Moebius in 1989. That same year he scripted a new take on a licensed character called Solarman (there was also a cartoon pilot for a show, but it was never picked up). And in 1991 he wrote a comic about a character called Nightcat, whose identity was real life singer Jacqueline Tavarez (there was even a Nightcat album).

Ravage 2099, then, was Lee’s first wholly new superhero concept in many years. The first issue introduces us to Paul-Phillip Ravage, of the “Commander” (akin to a CEO) of a company called ECO, whose mission is to fight pollution, seemingly by sending its bloodthirsty security force after “polluters” (again, in this future, corporations have essentially taken over public services). Trick is, they’re a subsidiary of Alchemex, a company that does most of the polluting.

This is an intriguing set-up, but Lee doesn’t seem all that interested in the inner workings or grander implications of the world he’s created. He only wants to get Paul-Phillip to his status as a kick-ass vigilante. So through a series of events not worth recounting, Paul-Phillip learns of his company’s misdeeds, gets framed by his boss, and is forced to go on the run.

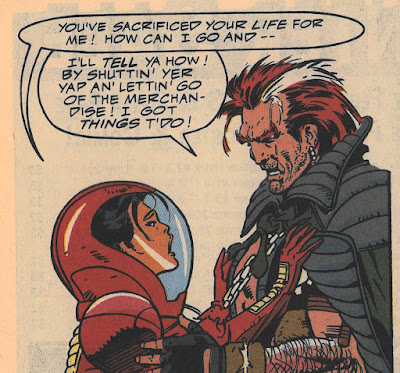

At the start of the story he’s a polished, articulate company man who believes in the system, but the trauma he experiences causes him to revert to a sort of primal state. By the end of the issue his hair is wild, he starts wearing a dagger earring, and he begins speaking like Ben Grimm (his dialogue is all dropped “g’s” and New York street grammar). I think Lee was going for some sort of Falling Down / Dirty Harry vibe, but it's a jarring transition. I wasn’t the only reader confused. In issue #6, the letters page featured a note from John D. Moon, who wrote “I fear, however, that when the naïve but sophisticated business-man became the savage pseudo-Wolverine, you lost a little of the character you had built so well in the first issue."

I’d go farther and say that they lost most of the character. Ravage is an extremely unlikeable individual. He’s unconcerned about committing murder, and he’s rude to those who are trying to aid him. This is especially true of his secretary, Tiana. Lee’s 1960s Marvel work has been justifiably scrutinized for its belittlement of female characters, with the Wasp and Invisible Girl particularly facing a steady barrage of derision and dismissal from the male superheroes in their lives. In Ravage 2099, Tiana is ostensibly a love interest. Paul-Phillip says in the first issue, “You know how I feel about you” and he twice goes to great lengths to rescue in the course of the first seven issues. But doesn’t seem to like or respect her at all. In fact, the way he talks to her is borderline abusive.

It’s difficult to guess what Lee thought he was accomplishing with Ravage 2099, but one thing that’s clear is that the book was a response to the explosive popularity of the Image artists, especially Liefeld. In a manifesto in the back of issue #3, Stan writes, “One thing you might have noticed about our first few issues, we’ve been trying to concentrate on the story line and character development as much as possible. At a time when everything in comics seems to move so fast and furiously, we felt we’d give our Ravage-ites a bit more copy to read, more panels per page to look at, and more time to mull things over and let the plot points sink in.”

This is a noble goal, and a not-so-subtle swipe at the direction comics were then headed, but it doesn’t actually play out in the comic. Ravage 2099 does have a classic look and style, but story-wise it’s is a very facile book. The environmental theme is all but forgotten after the first issue, and every chance to do something layered or complex is passed up. And with its constant action and violently one-dimensional protagonist, it actually reads like a failed attempt to replicate Liefeld's work, even down to the armored villain Dethstryk (about as '90s of a name as you can get, but odd since Marvel already had a character called Lady Deathstrike).

Ravage 2099 did have a sort of spiritual connection to the Image artists, though, in that they seemed to have shared the same inspiration: Stan Lee’s most famous collaborator, Jack Kirby. Rob Liefeld and Erik Larson, in particular, greatly admired Jack Kirby’s 1970s work, and tried to replicate that anything-goes energy in their books. Compared to, say, Youngblood or Savage Dragon, Ravage 2099 actually does a better job of capturing the frenetic, improvised feeling of Kirby’s work on books like Kamandi and OMAC. Partly that’s because those books were also set in the future, but it’s also thanks to artist and co-creator Paul Ryan.

Kirby’s self-written work sometimes lacked story logic, but made up for it with crazy ideas and mind-blowing visuals. Ryan’s work is nowhere near as inventive or dynamic as Kirby’s, but it has that same impeccable draftsmanship, design, and storytelling. Lee gave Ryan high praise in that same write-up in issue #3: “First I must congratulate Paul Ryan, one of the most talented and dedicated artists with whom I’ve ever collaborated. His every panel is so meticulously and painstakingly detailed, so lavishly endowed with colorful backgrounds and authentic costuming that I’d almost suspect he’s a time traveler from the future who is simply illustrating scenes that he’s already seen in 2099.”

I loved reading that. Ryan, one of those unfortunate people who has their name hijacked by a horrible human being, is one of my favorite comic book artists of all time, and is criminally underappreciated. A Massachusetts native, Ryan was a former National Guard member who worked at an engineering firm before landing a job as comics artist Bob Layton’s assistant in the mid-1980s. That led to inking and penciling work at Marvel, including Squadron Supreme, D.P.7, Quasar, Avengers, Iron Man, and Fantastic Four. Not only was his artwork detailed and solid, he was fast, which meant you often got two books worth of his artwork each month. For instance, while he was doing Ravage 2099, he was also working on Fantastic Four. His art on Ravage 2099 is, frankly, the only thing that makes the book readable.

Ryan exited Ravage

2099 after issue #7. Lee co-wrote #8 with the title’s new writers, Pat

Mills and Tony Skinner, before handing it off completely. Along with artists

Grant Miehm and Joe Bennett, they somehow managed to nurse the book along until issue

#33, which came out in August 1995. In that issue, Ravage is apparently killed by Doom after being encased in adamantium and shot into space. The 2099 line as a whole didn't survive either. All of the remaining titles were cancelled in August 1996, and the line was given an 8-issue miniseries (2099: World of Tomorrow) and one-shot (2099: Manifest Destiny) to wrap things up. Since then, 2099's most popular character, Spider-Man (Miguel O'Hara), has continued to pop up here and there.

*

I hate the false narrative that a creative person's skills inevitably go into decline as they age, and before re-reading Ravage 2099 for this project, I was prepared to put it forth as an example that Stan Lee still had some creative mojo in his later years. But now having re-read it, and having surveyed Stan's various attempts to create new superhero universes in the 1990s and 2000s, I'm inclined to say he was better off in the role of elder statesman, hype-man, and ambassador.

And I think he either knew that, or at least he recognized that those duties made it so he couldn't give 100% to writing a comic - one Ravage 2099 letter page tells a story of him writing a script for an issue in a hotel room in one night. So it's no surprise that Ravage 2099 would be Stan Lee's last extended work as a writer (a series of one-shots for DC in 2002 are the only thing that comes close). It's not an especially inspiring swan song. Lee was a

supremely talented writer and creator, but sometimes you just can’t go back, not even by going forward.

Comments

Post a Comment