The Best Fastest Man Alive

Flash #80

Writer: Mark Waid

Penciller: Mike Wieringo

Inker: Jose Marzan, Jr.

Colorist: Gina Going

Writer: Mark Waid

Penciller: Mike Wieringo

Inker: Jose Marzan, Jr.

Colorist: Gina Going

*

One of the best things to come out of DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths was the decision to have Wally West – the former Kid Flash – take over the mantle of the Flash. Wally became a Flash for the 1990s and early 2000s. He was a shining example of DC’s commitment to telling a multi-generational superhero saga, allowing its characters to grow and evolve along with its audience.

Like most of their best innovations of the 1980s and 1990s, DC eventually tied all of that to a rock and drowned it in a river. And so Wally West has had a rough go of it in the past 15 years. With 2006’s Infinite Crisis, he was shuffled off to an alternate reality, and DC tried to pass the Flash torch again, this time to Bart Allen. But his series proved unpopular, and Wally returned for a couple of years. Then 2009’s Flash: Rebirth found Wally sidelined by the unnecessary return of the first Flash, Barry Allen.

But it got worse. In 2011’s Flashpoint and its resultant “New 52” reset, he was written out of continuity and replaced by a completely different character with the same name. The 2016 “DC Rebirth” brought him back, only to find he’d been forgotten by his wife, and that his two children were lost somewhere outside of reality. This trauma eventually led him to have a breakdown and to involuntarily murder several of his fellow heroes, as depicted in 2018's Heroes in Crisis.

Wow, I got exhausted just writing that out.

Just as Wally was once the epitome of DC’s commitment to forward momentum, his egregious mistreatment is an encapsulation of DC’s regression in the 2010s, as well as yet another example of their determination to give every single character a backstory as tragic as Batman’s. What made this all the more difficult is that such fantastic work had gone into building Wally West up into someone truly admirable.

That work started in earnest the 1990s with writer Mark Waid.

Starting out as your typical bland 1960’s sidekick, Wally served as Teen Titan, went to college, and retired from superheroing. He was brought back reluctantly with 1980’s New Teen Titans, in which Marv Wolfman – who disliked the character – wrote him as exceedingly normal “mid-western conservative” who sometimes had little patience for his teammates’ eccentricities and hang-ups. (though to Wolfman’s credit he did devote a whole issue to showing Wally’s compassion for and understanding of his friends, New Teen Titans #20). Overall he was a character very much in the mold of his mentor, the straight-laced and humorless Barry Allen.

Wally’s time as the Flash began with his own title in 1987, with the team of writer Mike Baron and artists Jackson Guice and Mike Collins at the helm. They lasted about a year before William Messner-Loebs and Greg LaRoque took over for what would be a four-year run. Like many of DC’s post-Crisis books, the title was idiosyncratic. DC editorial at this time seemed to allow writers to really bring their personal visions and quirks, and in Messner-Loebs’s case that meant a strange brew of absurd elements and very real-world concerns.

Though I didn’t particularly love Messner-Loebs’s work on the title, I recognize he did some very important groundwork in allowing Wally to begin a journey of immense personal growth. He introduced the reformed and openly gay Pied Piper as a close ally, and he created Korean-American reporter Linda Park as a romantic interest. Most importantly, he showed Wally’s worldview expanding.

In 1992, with issue #62, Alabama native Waid took over. It was a pretty big assignment for someone whose only ongoing credit to that point had been with the ill-fated Impact line. Like so many writers before him, Waid had begun as an editor, but he quickly differentiated himself through his encyclopedic knowledge of DC (and Marvel) history. Starting with a “Year One,” story exploring Wally’s origin and psyche, Waid began what would be an eight-year epic about a man coming fully into his own, as a hero and as a human being.

In his time with Wally, Waid established an emotional life for the character, created one of the great love stories of the DC Universe, developed a mythology behind the Flash’s powers, and built an extended family of speedster heroes.

Flash #80 picks up in the aftermath of an epic storyline called “The Return of Barry Allen” that found Wally beginning to come out from under the shadow of his fallen mentor. The four-part “Back on Track” story concerned him confronting a different figure from his past, former girlfriend Frankie Kane. Turns out that Frankie’s magnetic powers are wreaking havoc on her brain chemistry, and this has brought out her anger at Wally for how their relationship ended. This forces Wally to acknowledge some of his less-than-admirable past behavior, and to make things right while also navigating the jealousy of Linda, who has now become his girlfriend.

The storyline's guest stars, Nightwing and Starfire, underscored Waid’s strength at drawing upon a character’s history in order to move things forward.

But Flash #80’s greatest significance come from who drew it. Greg Laroque had continued on the title in the switch from Messner-Loebs to Waid, but #80 featured the debut of a new regular penciller, a young man from Virginia named Mike Wieringo. Wieringo had literally three professional credits to his name before being given the keys to the Flash, and his style – clean and cartoony – was 100% out-of-step with what was popular at the time in mainstream superhero books. But because of that, and because his talent that became more apparent with each issue he drew, he stood out and would very swiftly become a comics superstar. In fact, he would be at the forefront of a back-to-basics movement in comic superhero art that wouldn’t fully take hold until the late 1990s.

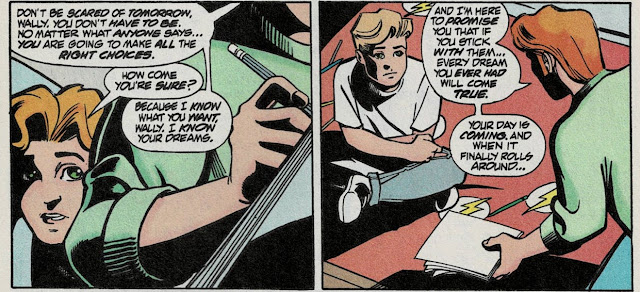

Waid and Wieringo's defining moment with Wally was Flash #0, cover-dated October 1994. As a result of the Zero Hour event, Wally finds himself revising his own past, and becomes corporeal enough to interact with his 10-year-old self, a dreamy kid whose parents are tough on him. And he's able to tell him what we'd all love to hear:

...It's gonna hit you like a bolt from the blue."

Wieringo would only stay a year on Flash, but had a great impact on the way Wally, his supporting cast, and the book itself were perceived from that point forward. He’d go on to work on Robin, Sensational Spider-Man, the creator-owned Tellos, and the Adventures of Superman to name a few. His crowning achievement was a beloved 2002-2005 run on Fantastic Four that reunited him with Mark Waid. Tragically, Wieringo died of an aortic dissection at the age of just 44.

*

Other than a short bit of time where Grant Morrison and Mark Miller wrote the title, Waid guided Wally’s adventures until 2000. At the time he shared that he felt he'd said all he had to say about the character. In the process of explaining that, Waid revealed what made his take on Wally work so very well: "The book's always been at its best when its been most personal - when I was using Wally to work out the difficulties and quandaries in my own life."

Geoff Johns took over next, building upon Waid’s character work with Wally, though it became clear early on that his greater interest was in developing and exploring the Flash’s villains. He did end his run with Wally becoming a father, a thread Waid picked up on during his brief return to the character from 2007 to 2009.

In 2001, the Justice League cartoon premiered on Cartoon Network. The Flash in the show? Wally West. Though more quippy (and horny) than Waid’s version, the TV version captured the essence and heart of the character, and became the definitive Flash for a generation of fans.

As of May 2021, with issue #768, Wally West is back as the primary Flash. Writer Jeremy Adams has assured us this is no trick, and that he won’t break our hearts, but he’ll have to forgive Wally West fans such as myself for not getting our hopes up just yet. It's probably too much to ask that Adams approach Wally's character development as thoughtfully and thoroughly as Waid and company did, but at this point I'd settle for him receding into the background with dignity.

*

Works Cited:

Wells, John. "Growing Up Fast." Back Issue #126 (April 2021).

Comments

Post a Comment